A year and a half ago, my girlfriend of seven years at the time (now fiancée) and I took a weekend trip to Carmel, California. Still in the throes of the pandemic, we were looking for an escape from the chaos of San Francisco so we rented a car and drove down to Carmel on the most beautiful road in America, the Pacific Coast Highway.

A couple of hours later, we were pulling up to our home for the next few days: a small loft in the Carmel Highlands (that we found on Airbnb) belonging to a family who had lived there for something like sixty five years. The loft was private but attached to a main house where the host, Lotte, lived with her daughter Naomi. My impression was that Naomi was now taking care of her mother and their home.

We took our belongings out of the trunk of the car and walked through the small garden along the front side of the house. I remember it being absolutely covered with flowers of every color; the whole front of the house was kissed by the gentle, orange shade that the sun so dutifully imparts on California’s coast every single evening. The garden was our first hint and as we walked in through the front door it became clear to us that this place was more than just a small loft: it was enchanted. It was magical.

The bottom floor of the loft absolutely littered with books, I would spend the next few days combing through the most esoteric and wide-ranging selection of literature that I had ever come across. I found Marcel Proust in the middle of a stack of books topped with the Constitution of the United States and spent an evening flipping through Jean-Francois Revel’s Without Marx or Jesus. In those shelves I encountered Nietzsche for the very first time and, fearfully but decisively, I pulled out a copy of Heidegger’s Existence and Being that was still dog-eared about halfway through.

Eventually I found a book that would go on to stay latent in the back of my mind for the next year and a half: Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me, a picaresque novel with a fantastic title that he derived from the Furry Lewis song I Will Turn Your Money Green.

But it was Fariña’s own name, not that of his novel, that stood out to me more than anything else. Sure enough, Wikipedia revealed that he was born to a Cuban father—a fact that practically forced me to read it. I read through the first fifty pages or so and I was immediately left with the feeling that this was different from the books that I usually read. It was strange and punchy, sexual and psychedelic and meandering, a totally foreign snapshot of the sixties:

“My name’s Pamela,” she told him, pouring through a wooden sieve into handleless cups. The robe open slightly at her throat, kitty-fluff parting enough to reveal a blond chest hair, which caused a spasm of lust.

“What school are you in?” between cups.

“Astronomy,” he lied. “Theories of origin, expanding galaxies, quantum mechanics, that sort of thing. You?”

***

A few weeks ago, I found myself gravitating back to Fariña’s first novel to finish what I had started. Unable to find anything on Amazon for under forty dollars, I was lucky enough to snag a used copy from my local bookstore of the 1971 edition that advertises the movie of the same name—it is tattered and broken and it smells like all old books do, but it was the only one that they had so I took it for a grand total of six bucks.

I came back into the world of Gnossos Pappadopoulis, Fariña’s Odyssean protagonist who’s life largely mirrors that of the author, because I had questions.

What was it like to live like the hippies did? Does a life like that eventually leave you saddled with regrets? What do kids who’s parents were hippies say? Or rather, if you read in between the lines:

As I immersed myself in Gnossos’ world, with its frat parties and its orgies and its mescaline trips and even its brief foray into the Cuban revolution, I started to zero-in on the truth: Gnossos and I, and by extension Fariña, have next-to-nothing in common.

This is somewhat of a scary realization for someone who is interested in a life well-lived because it means only one of us can be right.

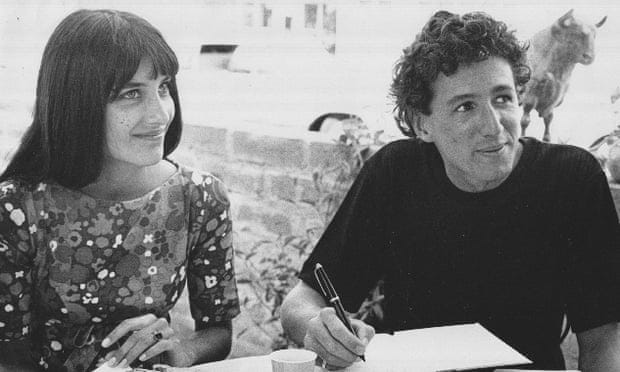

Who’s it going to be? The care-free, adventurous, drug-fueled beat hippie who married his first wife eighteen days after meeting her and then left her for a 17-year old (with whom he’d go on to record several influential folk albums), the same guy who eventually died in the Carmel Highlands at the age of twenty-nine when he flew off the back of a friend’s motorcycle going 92 miles per hour only two days after publishing his first novel, or me?

Unable to evoke response, Gnossos murmured, "Holy shit." and made his way to the bathroom. He locked and bolted the door, took down the Anatomy of Melancholy from the commode bookshelf, and lit his joint. For fire he rolled up the letter on the front page of the Sun and started it with a match. There's a time in the lives of men, came the thought, which taken at the tide you're liable to fucking drown.

At times, I found Fariña’s novel to be a bit of a slog. Too often was I finding it completely and hopelessly unrelatable: I have never tripped on psychedelics or participated in an orgy or gotten an STD or fought in anything even remotely close to a “revolution”. The raised fist just doesn’t do it for me, to be honest. It never has.

But soon I realized that my curiosity around Richard Fariña and Gnossos Pappadopoulis was actually just a real-world manifestation of the curiosity I have for my own life and life in general. I suppose this is true for all stories and is what makes reading books or watching films or experiencing art worthwhile. When I ask “Was Gnossos free?” what I am really asking is “Am I free?”

Richard Fariña flew too close to the sun and as a result the world lost a budding artist in a tragic accident, but am I flying too close to the sea?

What if I let myself fuck around a little more?

***

The problem with “fuck around and find out” is that you almost never want to find out.

Finding out often means dying, the blaze of the sun melting your feathers apart, which is obviously suboptimal. There is no need for a deep philosophical take here, this is self-explanatory, so let us cap our downside and take reasonably avoiding death as an axiom.1 If you are pretty sure you are not going to die, go ahead and find out.

Simple enough, I suppose. We are now left with only one more variable to solve for: fucking around.

In the midst of my hippie nostalgia I became interested in getting a tattoo. It became clear to me over discussions with friends that this was the perfect dry-run of how to solve for “fucking around”—not because it’s a particularly big deal (it’s not), but because it generalizes very well.

With each conversation, I was attempting to rationalize the decision:

“I want to test my ability to make a permanent decision,” I would often joke.

My favorite reply: “Aren’t you getting married?”

But it was one particular conversation with a friend that inched me closer to the truth. I could tell that he found my rationalistic probing into such a casual matter to be downright weird. I was trying to explain, very calmly:

“I’m trying to figure out why I want a tattoo.”

I hit send and as I continued to type I watched the typing indicator start to animate. He cut me off:

“I mean, because they’re cool.”

No other premise was provided, that was the premise. “Because they’re cool.” Is fucking around that simple?

***

Since the time of Aristotle, science and rationality have suffered from what is called the Regress Problem. Consider the following premises, straight from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Whatever is scientifically known must be demonstrated.

The premises of a demonstration must be scientifically known.

Now, run the algorithm. In order to “scientifically know” a given conclusion, you must demonstrate its premises—so you find the premises backing your conclusion’s initial premises and demonstrate those, which requires finding the premises backing those premises and demonstrating those, which requires…

This is called infinite regress. The process goes on forever and nothing can be demonstrated, therefore knowledge does not exist.

Well, not quite. There are solutions to this age-old problem, but only for conclusions that lie in the scientific realm to begin with and getting a tattoo is not one of them. In fact, nothing that one can consider “fucking around” is within reach here.2

To solve for “fucking around”, we need other faculties. Or, more specifically, if we’re interested in rationalizing it then we need a new premise. We need a first principle, a base case for the recursive algorithm.

We can invent our own rules to rationally think through the irrational and terminate the regress problem. In the case of “fucking around”, all we need is one very simple but profound premise: fun is a terminal value.3

The use of the word terminal here is not a coincidence—to the more rationalistic-minded person, this premise serves to terminate the regress problem. That is what makes it terminal; this is what it means to think logically. Fun is a first principle, one that requires no further premises and is on its own a self-evident truth.

Problem solved, “fucking around” unlocked.

Now, I realize that you might be reading this and thinking to yourself:

“Damn, what kind of fucking loser has to think this way about every single little thing?”

Not a problem. If “fun is a terminal value” does not resonate with you, there is another way.

***

If you’re so smart why haven’t you stopped thinking?

For months now, I have been thinking a lot about thinking less and it turns out that vibemaxxing is one of those things that you cannot unsee.

Ever since The Enlightenment crowned rationality king, humans began to accrue counterexamples—moments where we realized that instead of thinking more what we actually need to do is think less.

Friedrich Nietzsche is one such example—he took the Ancient Greek meme of the Apollonian and the Dionysian (in short: rational thinking and order vs irrationality and chaos) and fully subsumed it into his whole being, even going as far as to refer to himself as Dionysos towards the end of his life. He may have ended up going insane, but I like to think that he had an intuition about what would happen to society if we all suddenly started thinking too much.

From Rüdiger Safranski’s Nietzsche:

Even though science is to be commended for cooling down our passions, it should not take this process too far. Society is threatened not only by unbridled passions but also by the prospect of paralysis once science has tempered them.

Rationality is here to serve us, not to paralyze us, and if rationalizing your way out of the irrational feels dumb or cringe, consider thinking less instead: the line between Apollo and Dionysus cuts through us all.

***

Of everything that I found while I was reading about Fariña nothing stood out to me more than a screenshot of the loft’s description on Airbnb. I found it on my phone last week, while looking back at my trip to Carmel.

On its own it was enough to make sense of all of this, from the enchanted feeling the loft gave me to the fact that of all the books I flipped through that weekend what I was left thinking about a whole two years later was Richard Fariña and his Odyssean protagonist. It reads:

If you are a naturalist, an artist, a dreamer, reader, writer, a contemplative, a hard worker in need of a weekend retreat, if you wish to be quiet, to romance, this is your place. We prefer to rent to 2 adults and/or 1 extra person.

In the 60's this studio was home to folk duet Mimi and Richard Fariña, jazz guitarists, painters and dancers. Famed local photographer Brett Weston praised its quietude and its location as "magical."

I’m not one for superstition, but maybe it was the ghost of Fariña who taught me that it does not matter how we choose to rationalize “fucking around” so long as we do, because living intensely calls for it.4

I think I might fuck around and get a tattoo?

I enjoyed this tweet: reasonably avoiding death is the least that most of us could do for our parents.

There are many other areas in life where this is true as well. Consider love, for example. I will write more about this soon.

This meme, “fun is a terminal value”, seems to have been born from something David Deutsch calls the Fun Criterion.