One more thing…

You are earlier on the production curve than you think.

Welcome to A Work in Progress. This is not a “newsletter”—I do not publish on a regular cadence or about any particular topic; sometimes I write essays and sometimes I write poems. If you’re reading this because you are a subscriber, thank you for following along. I also want to welcome all of my new subscribers coming from the inimitable Pluripotent—hope you enjoy!

I’m thinking about marginal utility and the law of diminishing returns. This is a slightly different flavor of post than my usual, but I’d like to try it out and see how it goes. I think we’ve been sort of trained to think in these economics terms writ large, but it turns out that in real life these types of heuristics are not very helpful. In fact, in the context of our everyday lives we should ignore this type of advice entirely.

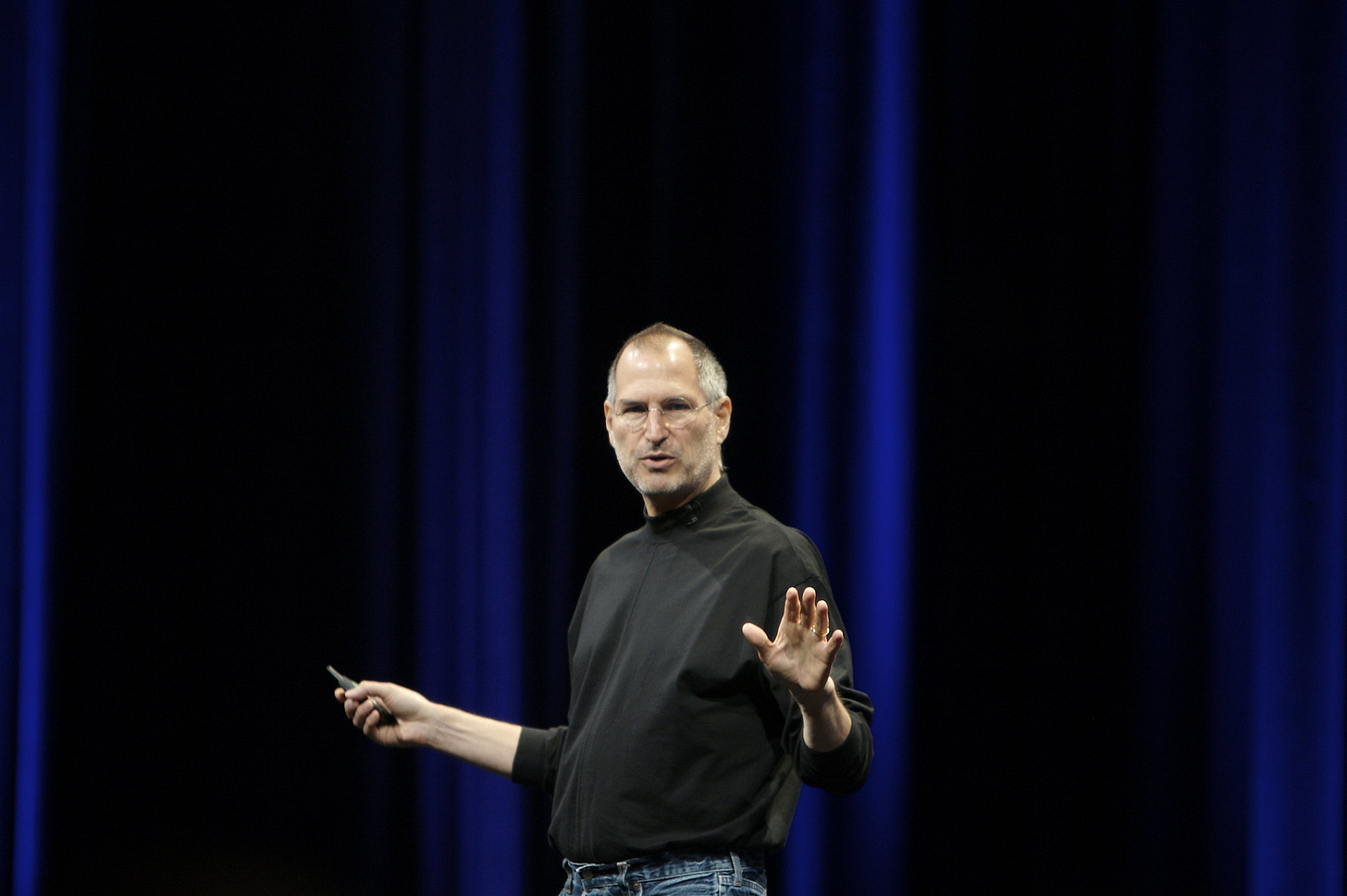

Steve Jobs was the greatest keynote speaker of all time. So much so, in fact, that his keynotes colloquially came to be known as Stevenotes. The only image on the Wikipedia page for “keynote” features Jobs on stage at Macworld in 2005, where he introduced the Mac Mini, the iPod shuffle, and iWork. Steve Jobs is synonymous with the very notion and essence of a keynote presentation, much in the same way that a Kleenex is a tissue or a Bandaid is a bandage.

Over the course of thirteen years at Apple, after an eleven year hiatus, Jobs perfected the keynote. His presentations were most famous for their closing segments, in which Jobs would, like a musician on stage at a concert, often feign that the show was over only to return and deliver a final encore. “But there’s one more thing…” he would often say, the crowd always roaring with excitement as they anticipated the grand reveal.

It was in this final segment, this one more thing, that some of Apple’s most iconic products were announced over the years. Everything from Apple TV to the Apple Watch and the iPhone X or the M1 Chip—this one more thing is where Jobs crowned himself the king of keynotes.

It just so happens that the value of one more thing has been a hotly contested question since the earliest days of economics, since the time of men like Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Most everybody has heard of the concept of diminishing returns (and its closely related cousin marginal utility but let’s ignore that one for now). In short, the value or productivity derived from adding one more thing is generally said to plateau over time as the quantity of things increases, eventually even going as far as to result in negative returns.

To help us understand this phenomenon, Wikipedia presents us with a thought experiment. Imagine a factory floor, and hold all factors relevant to production constant except for the number of workers. You’re not allowed to change anything else about the factory—technology, space, etc. Your goal is to increase the productivity of the factory, like the good capitalist that you are, but the only way you can do that is by increasing or decreasing the amount of workers. Early on, as you go from one worker to two workers to five workers, productivity increases proportionally with each new worker. Eventually, however, you inevitably end up with what is commonly described as having “too many cooks in the kitchen.”

However, if we look further along the production curve to, for example 100 employees, floor space is likely getting crowded, there are too many people operating the machines and in the building, and workers are getting in each other's way. Increasing the number of employees by two percent (from 100 to 102 employees) would increase output by less than two percent and this is called "diminishing returns."

This sort of thinking has bled far outside of the realm of economics, so much so that the value of one more thing is largely disregarded. Small, marginal changes are grossly underrated in everyday life. The issue here, generally speaking, is that real life deals with low volumes—human-scale volumes, not factory-scale volumes—and human-scale volumes are ripe with marginal returns.

To hammer the point home, here’s an example. Let’s pretend that you exercise 3 days a week. You have a consistent and reliable workout routine, and this seems fine to you. In fact, you’re very happy with it. That said, you could choose to exercise 4 days a week, which would result in a 33% increase in the number of workouts and all you have to do is add one more day to your already consistent workout routine. Over the course of a sufficiently long time period, say a year, this relatively simple change results in you having completed 52 more workouts. In the real world, simple, incremental changes can deliver outsized value. It’s not that hard to workout one more day, is it?

You are earlier on the production curve than you think. Ask yourself if there is, in fact, one more thing. The point of maximum yield is on the horizon, but who do you know has ever fallen off the edge of the Earth?