Leonardo da Vinci was a recalcitrant heretic. An unabashedly gay bastard born in 1452 to an orphaned and impoverished sixteen-year-old local peasant girl, he was marked with the seal of heterodoxy since the very moment of his birth. As a self-taught, “unlettered man” unable to attend any sort of formal schooling due to having been born out of wedlock, he would go on to call himself a disciple of experience—disscepolo della sperientia.1

A Disciple of Experience

It is this thirst to disregard authority and use his own eyes that “saved him from being an acolyte of traditional thinking.” Leonardo writes in his one of his notebooks:

I am fully aware that my not being a man of letters may cause certain presumptuous people to think that they may with reason blame me, alleging that I am a man without learning. Foolish folk! … They strut about puffed up and pompous, decked out and adorned not with their own labors, but by those of others. ... They will say that because I have no book learning I cannot properly express what I desire to describe but they do not know that my subjects require experience rather than the words of others.

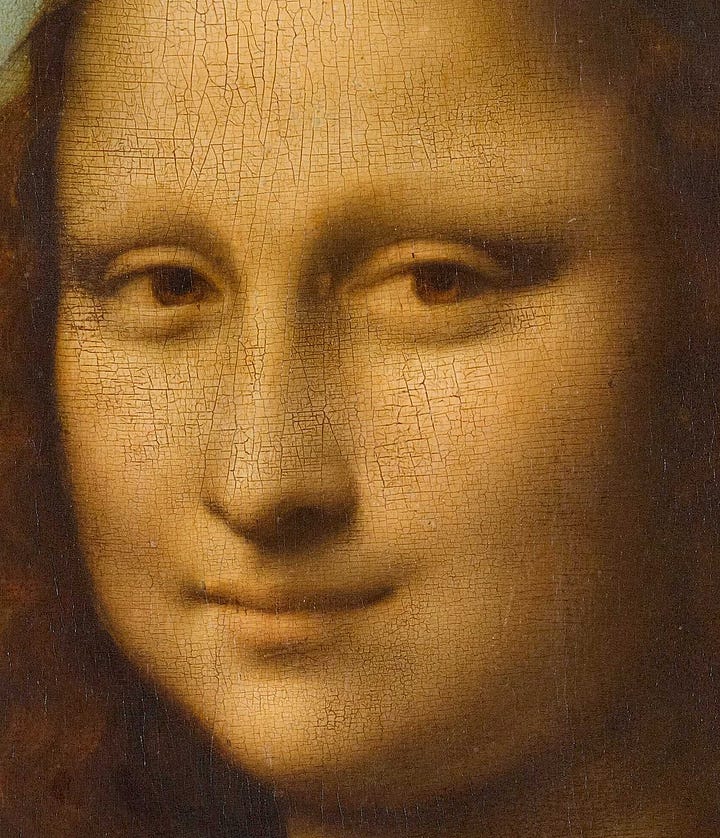

Born free from the chains of sociocultural and even artistic norms, Leonardo deviated from them often, sometimes even going as far as to repudiate them entirely. Leonardo pioneered sfumato, a technique characterized by blurred contours and soft, gradual transitions between colors—a clear repudiation of tradition and the status quo in favor of an empirical look at reality.

Only a freethinking heretic can take what seems like an axiom to an innocent observer of the arts and completely invert it. Leonardo, fenced in by the contour line, evaluated the world with his own eyes and chose to rebel. It is this act of rebellion that gave birth to the Mona Lisa, her eyes being the epitome of sfumatura.

Leonardo’s individualist streak, however, bleeds out from the canvas and onto the fabric of his life. There is no better way to illustrate this than to compare him to a fellow great of the Italian Renaissance and a bitter rival of his, Michelangelo Buonarroti.

A generation younger, Michelangelo was in many ways the antithesis to everything that Leonardo stood for. Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo’s biographer, wrote that Michelangelo displayed “a very great disdain towards Leonardo.” They could not be more different, Isaacson tells us:

Whereas Leonardo was disinterested in personal religious practice, Michelangelo was a pious Christian who found himself convulsed by the agony and the ecstasy of faith. They were both gay, but Michelangelo was tormented and apparently imposed celibacy on himself, whereas Leonardo was quite comfortable and open about having male companions. Leonardo took delight in clothes, sporting colorful shot tunics and fur-lined cloaks. Michelangelo was ascetic in dress and demeanor; he slept in his dusty studio, rarely bathed or removed his dog-skin shoes, and dined on bread crusts.

Asceticism can still produce great art, as is clear from the work of Michelangelo, but a closer look shows us what a worldview can do to a brush. In 1503, Florence's Great Council—headed by Pier Soderini, who was by advised none other than Niccolò Machiavelli himself—commissioned Leonardo to paint “a sprawling battle scene in the Palazzo della Signoria” that could have become “one of the most important of his life” had he not eventually abandoned the mural.2

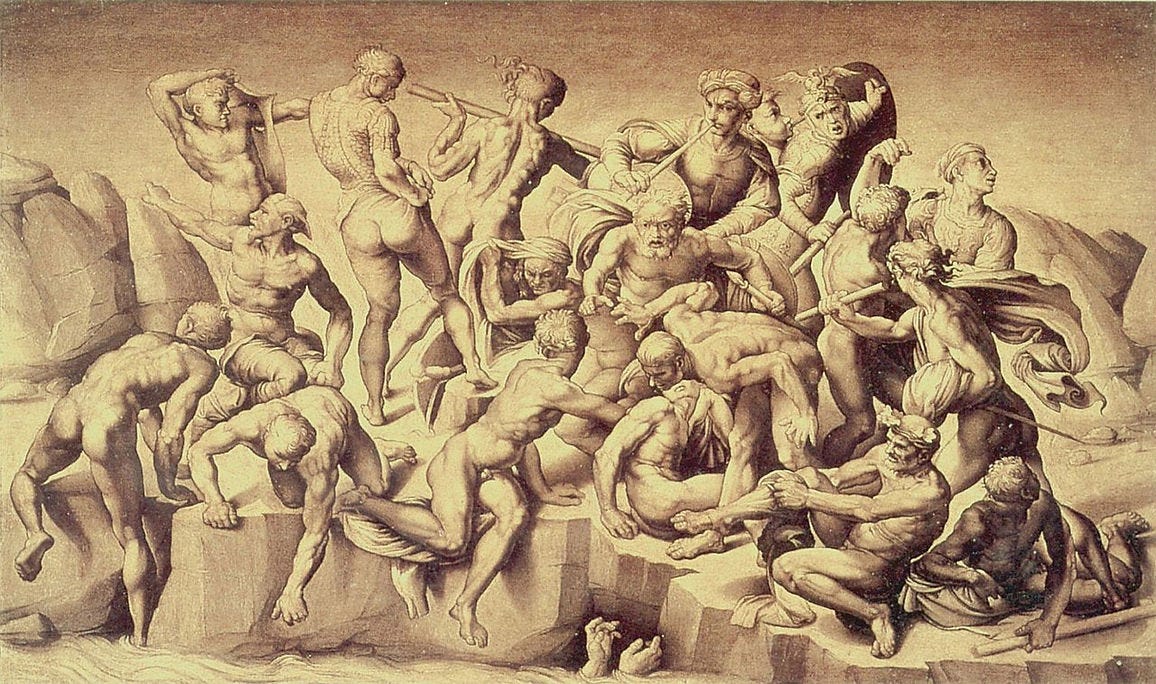

In 1504, a year after Leonardo had gotten started, Soderini slyly commissioned Michelangelo to paint a second battle scene in the Palazzo that would be “a companion to Leonardo’s in the great hall.” The spirit behind this decision was obviously to spur a competition between two of the great rivals of the Italian Renaissance. To his credit, Michelangelo also made an unorthodox choice when asked to paint the Battle of Cascina.3

He decided to forego a battle scene entirely, instead opting to paint a group of naked soldiers bathing in a river moments before they were ambushed. The stylistic differences in Michelangelo’s painting compared to anything Leonardo has painted are obvious even to a lay person like myself, but the best critique of its merits comes directly from Leonardo:

Leonardo rarely criticized other painters, but after seeing Michelangelo's bathing nudes he repeatedly disparaged what he called the “anatomical painter.” Clearly referring to his rival, he mocked those who “draw their nude figures looking like wood, devoid of grace, so that you would think you were looking at a sack of walnuts rather than the human form, or a bundle of radishes rather than the muscles of figures.”

Michelangelo, Leonardo claims, painted like a sculptor—exactly what you would expect from a traditionally-minded artist who instead of looking at the world empirically and thinking from first principles preferred to follow the rules-based order that he was born into.4 This is, of course, the sort of criticism you would anticipate hearing from a radical heretic who during his anatomical studies even went as far as to dissect bodies himself in order to better inform his art.

Behind Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, Florence’s military victory over Milan in 1440, lies a second story that again illustrates our Nietzschean protagonist’s dedication to non-conformity. Leonardo had “intense, conflicted feelings about war” and “aimed to create something more profound”—an ordinary depiction of Florentine glory on the battlefield was not enough for him. Isaacson tells us of the preparation in the Palazzo (emphasis mine):

Machiavelli's secretary Agostino Vespucci provided Leonardo with a long narrative description of the original battle, including a blow-by-blow chronicle involving forty squadrons of cavalry and two thousand foot soldiers. Leonardo dutifully placed the account in his notebook (using a spare bit of the page to draw a new idea for hinged wings of a flying machine), and then proceeded to ignore it.

Imagine having the wherewithal to sit through the entirety of what was likely a fiery and passionate lecture from the secretary to the father of modern political philosophy and political science (who is also a friend of yours!), only to ignore the entire fucking thing because frankly you’re just not that interested. Instead, you want to depict the human experience of war, the way it feels and the bitter ugliness that underlies it all, that “most beastly madness.” Your proximity to the madman that was Cesare Borgia permanently colored your thoughts, of which you had plenty, having written a detailed 1000-word account ten years earlier describing how you’d paint such a scene. Your notebooks are littered with intricate studies of men in battle, even going as far as to consider the emotions emanating from the faces of the war horses themselves.

Allegedly the painting was permanently damaged by a storm, causing Leonardo to eventually abandon it (a habit that he was incredibly comfortable with, having only ever finished a handful of paintings). Disappointing as it may be for the rest of us who would love to enjoy more completed works by Leonardo, his refusal to stay beholden to expectations set by others and instead abandon paintings at-will is another salient example of his independent-mindedness. Today we are left with nothing but a copy of the Battle of Anghiari painted by Peter Paul Rubens:

Nietzsche’s Noble Man

We arrive at our central question. Does creativity call for heresy?

Through his life and what remains of his art, Leonardo left us with an example of art fueled by heterodoxy and a worldview imbued with a desire to look at the world with one’s own eyes and evaluate it from experience. There is no single path to creativity, as is shown by Michelangelo, but it is hard not to draw a causal relationship between Leonardo’s way of looking at the world and the indelible mark that he left on it. Isaacson himself certainly draws this conclusion:

As a gay, illegitimate artist twice accused of sodomy, he knew what it was like to be regarded, and to regard yourself, as different. But as with many artists, that turned out to be more an asset than a hindrance.

And it is not a bad one to draw. As with many contentious topics and profound questions, we can look towards philosophy for an answer. This relationship between heresy and creativity is exactly what led Friedrich Nietzsche to question morality and altogether reject it wholesale. Nietzsche glorified heretical men who looked at the world and evaluated it for themselves, his preferred examples being men like Napoleon, Goethe, and Beethoven. I am surprised that he did not mention Leonardo alongside of them.

In Leonardo we find Nietzsche’s noble man:5

The noble type of man feels himself to be the determiner of values, he does not need to be approved of, he judges “what harms me is harmful in itself”, he knows himself to be that which in general first accords honour to things, he creates values.

Everything he knows to be part of himself, he honours: such a morality is self-glorification. In the foreground stands the feeling of plenitude, of power which seeks to overflow, the happiness of high tension, the consciousness of a wealth which would like to give away and bestow.

Nietzsche was worried about morality and the “instinct of obedience” running wild and being taken to some final extreme:

If we think of this instinct taken to its ultimate extravagance there would be no commanders or independent men at all; or, if they existed, they would suffer from a bad conscience and in order to be able to command would have to practise a deceit upon themselves: the deceit, that is, that they too were only obeying.

An overzealous adherence to morality, Nietzsche claims, would neuter the creative instinct. In other words, he believed that creativity (and greatness in general) does in fact call for heresy. Regardless of whether or not you fully endorse Nietzschean ethics, a look at Leonardo’s life vindicates Nietzsche in his obsessive preoccupation with morality. A more traditionally-minded Leonardo would have painted like Michelangelo, relying on contour lines instead of looking at the world around him with his own eyes and seeing that it calls for sfumatura.

A disscepolo della sperientia feels themselves to be the determiner of values. He goes beyond tradition and deeper than state-sponsored depictions of Florentine glory. He sports colorful shot tunics and fur-lined cloaks and is twice accused of sodomy. He dismisses men of letters as presumptuous, opting to instead use his own eyes. He does not stop at surface-level anatomy, instead he dissects bodies himself—editing a painting thirty years after having started it when he discovers that the sternocleidomastoid is actually two muscles.

Fundamental to Leonardo’s creativity was his heretical nature. Without heterodoxy, there is no Renaissance. Without a disrespect for contour lines, there is no sfumato. All rules are arbitrary. Now, go do with that what you wish.6

Isaacson, Walter. Leonardo da Vinci. Simon & Schuster, 2017

All quotes that follow if not annotated are from Isaacson’s biography. I read it a few years ago and still to this day think about it often. Consider this a very strong recommendation!

For another account of the drama at the Palazzo, I recommend this essay that I found after a quick Google.

Funny enough, Michelangelo also failed to complete the Battle of Cascina.

That said, to Michelangelo’s credit, he himself acknowledged his own shortcomings with the brush:

Michelangelo was good at delineating forms with the use of sharp lines, but he showed little skill with the subtleties of sfumato, shadings, refracted lights, soft visuals, or changing color perspectives. He freely admitted that he preferred the chisel to the brush. “I am not in the right place, and I am not a painter,” he confessed in a poem when he embarked on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel a few years later.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil. Penguin Classics, 1973

There exists a fun tension here: this does not call for you to adopt Nietzschean ethics wholesale or abandon tradition and morality entirely. Doing this blindly, I believe, would be worthy of the same exact Nietzschean critique that he himself gives traditional morality. I’ve taken all of this to mean that you should simply think about things for yourself. There is a relevant quote from Jose Martí that has stuck with me forever:

I don't ask you to believe what I believe. Read what I say, and believe it if it seems right to you. The first duty of man is to think for himself. Therefore I don't want you to believe your priest; because he won't let you think.

And, despite this, Martí was religious! See the next underline in the linked tweet.