One of the thirty or so brothers stood underneath an archway along the side of the monastery. As we got closer, I realized that he was waiting for us. We had a tour guide.

He met us halfway and as he walked towards us I could not help but notice the peaceful demeanor with which he took each and every step, almost as if he was gliding across the floor.

We had been haggling with the security guard just a few minutes earlier. Behind the monastery, or rather in front of it sitting proudly at the edge of a cliff in the mountains of Medellín, a church was being erected. Mass at the chapel in the monastery was not until later in the afternoon, the guard would inform us, but we were looking to get married and curious about the monastery and the church’s construction timelines. A brief exchange occurred over radio and the gate was opened.

The brother greeted us warmly, asking us if we would like to go see the church.

He was wearing a beige tunic with dark brown accents, almost exactly what I imagined a Catholic monk would be wearing if I ever got to meet one, with an ornate figure of the Virgin Mary on his left breast and a chain around his waist with a Rosary attached to it. His head was shaved, but not fully, and his black boots went halfway up his shins. After a few minutes of conversation I deduced that he was about twenty-three years old, having arrived at the monastery ten years ago at the tender age of thirteen.

I figured he would walk us out to the plaza in between the church and the monastery and share a bit about his order, Los Caballeros de la Virgen, maybe show us around the outside of the monastery if we were lucky, and send us on our way.

But when we approached the foot of the church, with a few of its smaller gothic steeples already stretching towards the heavens, he directed us towards the hard hats hanging on hooks to the left of the door.

“Nothing is going to fall on us, but we have to wear these.”

The last thing I expected was to go inside of a church that was in the middle of being constructed, still about six months away from completion, with a monk wearing a hard hat. I untied my hair and placed the hard hat on my head.

As we walked in I did what everyone does when they walk into a large cathedral: I looked up. I was immediately struck by the strong and beautiful shade of crimson that covered every inch of the ceiling.

The sea of red was sprinkled with an intricate pattern of gold detail and there was a blue accent along the ribs of the vaulted ceiling. The church was entirely hand painted, the brother explained as we stood underneath the scaffolding that gave the painters access to their canvas.

“Do you see the Gothic architecture? Isn’t it beautiful? Our founder says that Heaven is gothic. El Cielo es gótico.”

***

We followed the brother out of the church and back into the plaza, making sure to hang our hard hats on their hooks. He walked us towards a gated fence bordering a smaller plaza that was enclosed on its remaining three sides by the monastery.

I asked if he could show us inside, to which he replied, “Of course. The gate is open. Follow me.”

He showed us inside of the small chapel. I genuflected as I walked in and then stood still alongside the last pew, unclear if I should proceed towards the altar. He quietly motioned us forward and I got the sense that he did not understand why we were all so unsure of what to do next. The three of us slowly walked towards the altar as he glided alongside us. Guessing that I would be reprimanded but having decided that it was worth the risk, I quickly pulled out my phone and took a photo.

Behind the altar were two statues, one of Saint Joseph and the other of Saint Raphael. All of us whispering now, the brother told us of a miracle that occurred some years ago with two young boys at the monastery. They were on their knees praying in front of the altar when one of them got up. The other boy, still kneeling in front of the altar, called back at his friend.

“Do you see those tears? Saint Joseph is crying.”

Both boys saw tears streaming down the face of Saint Joseph, or so the story goes.

The brothers in the monastery asked God for a sign, desperate to explain the little boys’ tale. A few days later, the brother told us, they all saw tears streaming down the face of Saint Raphael. The monastery brought in experts to try and explain the water running down the eyes on the faces of the statues but, allegedly, they failed to explain the phenomenon.

Quietly, we walked back out of the chapel and as we stood outside he explained to us the ways in which the body and the soul are intertwined.

***

As the brother continued to tell us stories and walk us through the rest of the monastery, the dining room where the boys and brothers eat and the school where boys as young as ten years old attend classes, I kept remarking to him how beautiful the building was. It was the only thing I could say, constantly reassuring him of something that he already knew to be true.

“Beauty is absolute,” he replied.

“Someone can tell you that they do not like the color orange or the color purple, but in the morning when the sun is born and they look up at the sky painted with streaks of orange and purple, they will say that it is beautiful. Beauty is irrefutable. La belleza es innegable.”

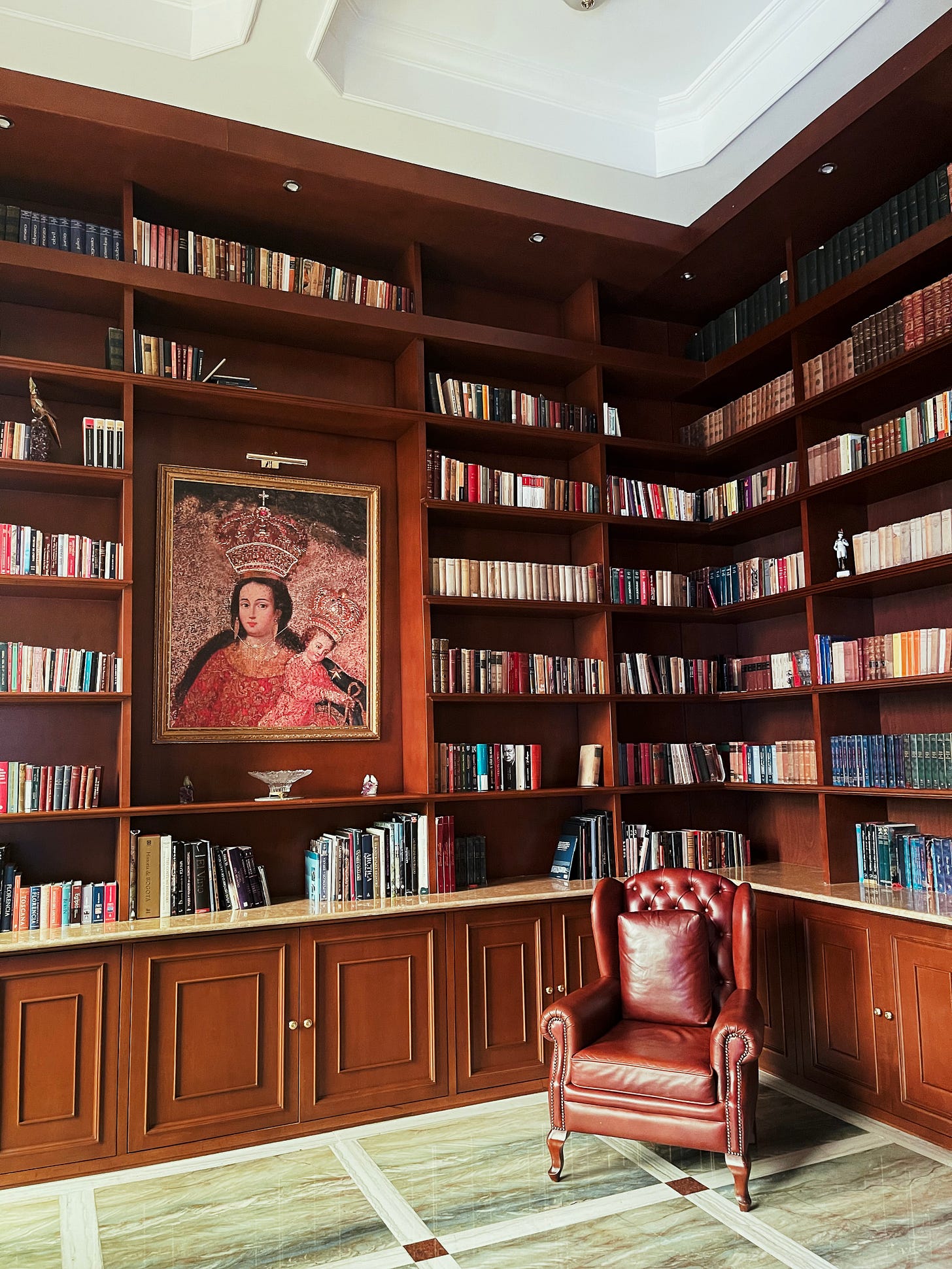

The monastery was the most beautiful building in Medellín, I was sure of it. The columns, the archways, the marble floors, the statues, the windows and the gates but especially the library with everything from El Magisterio de la Iglesia and Las Cuatro Mujeres de Felipe II to a Spanish translation of Andrew Roberts’ Churchill.

They do not build buildings like this anymore, I thought to myself, except for the church on the other side of the plaza.

I may have vocalized this thought, I do not remember, or maybe the brother saw it in my eyes as I scanned the archways of the monastery, but he turned to me as peacefully as he did everything else and replied:

“Why build something ugly? That does not make any sense.”